Learning in networks#

Basic ideas about networks#

Extending our discussions in the past week, I created a video to elaborate on a number of basic ideas about networks and social networks.

Learning in networks#

This week, we are focused on thinking about learning in or through networks.

The use of network analysis to examine learning needs to be informed by theories of learning and contexts in which learning happens.

During this week, you are engaged to explore several different theories that emphasize a “network worldview” and are widely applied to guide network analysis.

Required readings:

Haythornthwaite, C. (2015). Rethinking learning spaces: Networks, structures, and possibilities for learning in the twenty-first century. Communication Research and Practice, 1(4), 292–306. https://doi.org/10.1080/22041451.2015.1105773

Jones, C. (2015). Networked learning: An educational paradigm for the age of digital networks (Ch. 3). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-01934-5

Poquet, O., & Chen, B. (2024). Integrating Theories of Learning and Social Networks in Learning Analytics. In K. Bartimote, S. K. Howard, & D. Gašević (Eds.), Theory Informing and Arising from Learning Analytics (pp. 139–151). Springer Nature Switzerland. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-60571-0_9

Theories of learning in networks#

Network analysis of learning does not necessitate network-based theories of learning. For example, researchers can assess a learner’s knowledge by analyzing concept maps generated by students [Siew, 2019]. This use of network analysis does not involve consideration of learning in or through networks.

However, there are learning theories that conceptualize learning from a network perspective. In other words, they have distint opinions about how learning is fundamentally a network process, how networks support learning, and/or how learning shapes networks. Exploring these theoretical ideas would help in two ways:

Theories of learning would help unleash the full potential of network analysis. While network analysis techniques are helpful, theories of learning that bring a network perspective provide additional tools for network analysts to grapple with the learning phenonemon.

Theories of learning would provide grounding for network construction. As explained in Haythornthwaite (2015) and Poquet & Chen (in press), constructing networks from learning data is not always straightforward. Theories of learning offer guidance and justification for the construciton of network models to represent learning.

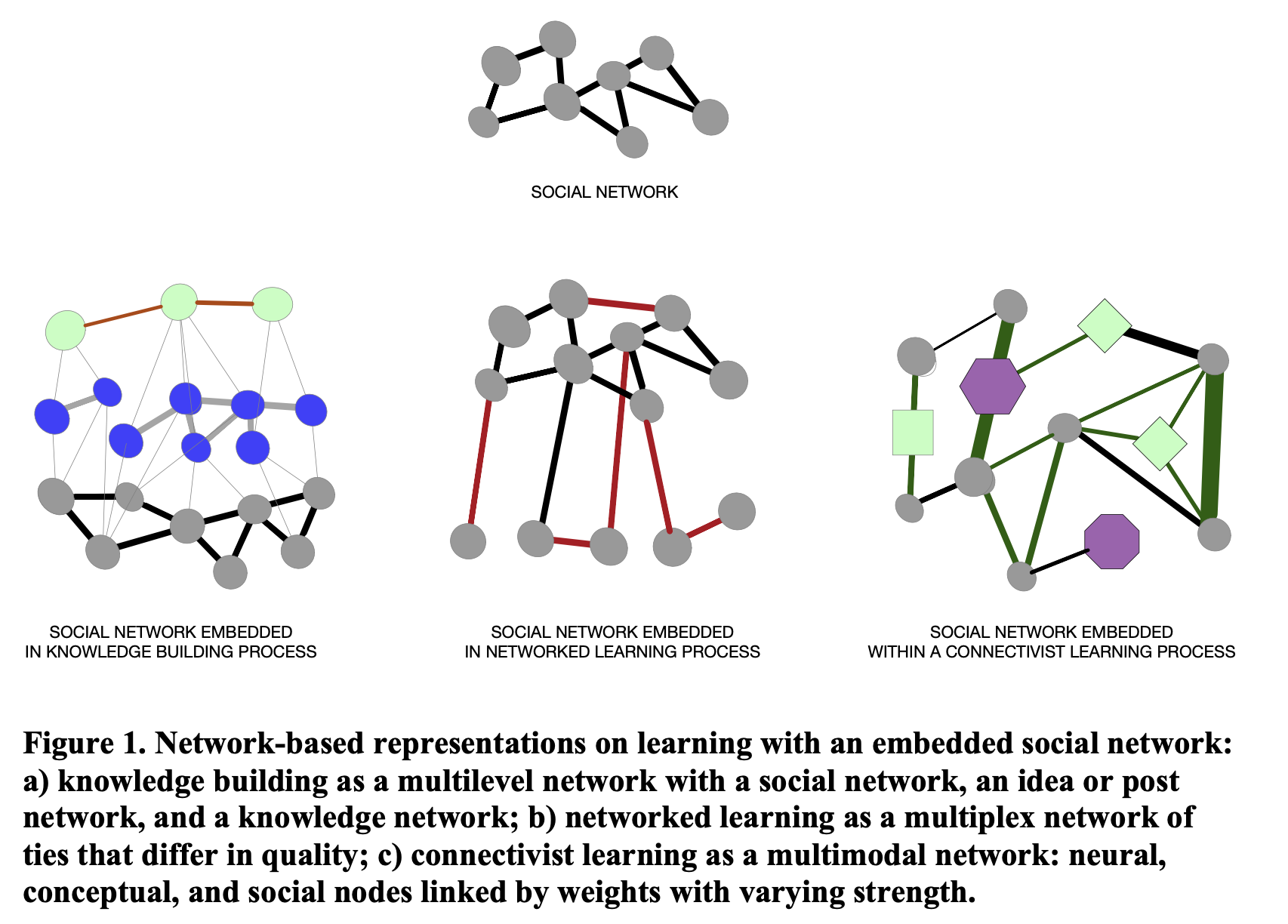

As illustrated by this figure from Poquet & Chen (2024), a social network of learners can be constructed in different ways based on distinctive views of learning including knowledge building, networked learning, and connectivism.

At the core of each network model, we ask: What is about the generative processes of learning according to the network-based view of learning? The answer to this question differs across these three theories.

Knowledge building emphasizes the interaction between ideas and people

Networked learning cares about content relationships and and situations where they form

Connectivism considers learning as connecting, and cares the “pipe” more than “content in the pipe”

Three levels of consideration when applying network analysis to learning#

Our discussion is aluding to three levels of considerations that researchers often need to be aware of. You could find more information in text such as [Niglas, 2010] or some other research methodology courses. Please note that this framework was constructed to help us grapple with the complex terrain of research, and it is highly debatable.

P#

philosophy, worldviews, paradigms

M#

methodology

m#

methods/techniques

Below, I try to explain these three levels of considerations:

m, or methods/techniques: The “small m” in SNA constitutes methods or techniques we apply in SNA research. Imagine we are using SNA to investigate friendship of a network of high-schoolers (think about “Gossip Girls” if you’ve watched that TV series). A technique in this SNA research could be a questionnaire used to collect friendship data among students; it could be the force-directed layout we use to visualize this network; it could be the measure of betweenness centrality we use to characterize high-schoolers; it could also be a network modeling algorithm we apply to model the flow of gossips. In a nutshell, these techniques are more about what we concretely do in an SNA research.

M: When SNA is referred to as a “big M” Methodology, it is treated as a systematic approach of investigating a phenomenon. Beyond simply applying these techniques, a methodology is also concerned with why a technique gets used. In other words, understanding SNA as a methodology means learning to make informed decisions in any stage of an SNA project. For example, why using a questionnaire instead of observations or interviews? In which cases should one use a circle layout instead of a force-directed layout? Why a specific SNA measure is appropriate for addressing a research question? In a nutshell, the big M is concerned with how knowledge could be best gained by following many SNA methodologists and researchers have created so far.

P, worldviews, philosophical schools of thoughts, paradigms: In SNA, some scholars go further to argue SNA offers a unique way of “seeing the world.” In Carolan (2014) chapter 2 you will read about the relational perspective that represent a particular worldview that emphasizes relations instead of attributes. You will also read about relational realism that is referred to as an ontology grounding SNA. To a great extent, SNA offers a new research paradigm. As put by Barry Wellman, a guru in SNA from the University of Toronto, “It is a comprehensive paradigmatic way of taking social structure seriously by studying directly how patterns of ties allocate resources in a social system” (see, Carolan, 2014, p. 33).

In this course, we are mostly concerned with the “big M” level. We will not dive too deep into the P level, and we will not settle with specific techniques. Together, we will learn how to apply various techniques to systematically produce knowledge about a phenomenon.

Also, SNA (or network analysis in general) does not need to be quantitative. As a matter of fact, SNA grew, in large part, out of the efforts of ethnographers to make sense of complex relational data. While modern SNA provides strong support for quantitative inquiry, SNA can be combined with qualitative methods in various ways.